What is an API?

An application-programming interface (API) is a set of programming instructions and standards for accessing a Web-based software application or Web tool. A software company releases its API to the public so that other software developers can design products that are powered by its service.

For example, Amazon.com released its API so that Web site developers could more easily access Amazon's product information. Using the Amazon API, a third party Web site can post direct links to Amazon products with updated prices and an option to "buy now."

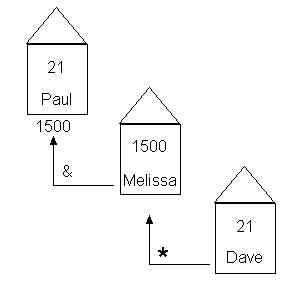

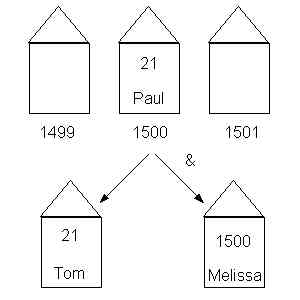

An API is a software-to-software interface, not a user interface. With APIs, applications talk to each other without any user knowledge or intervention. When you buy movie tickets online and enter your credit card information, the movie ticket Web site uses an API to send your credit card information to a remote application that verifies whether your information is correct. Once payment is confirmed, the remote application sends a response back to the movie ticket Web site saying it's OK to issue the tickets.

As a user, you only see one interface -- the movie ticket Web site -- but behind the scenes, many applications are working together using APIs. This type of integration is called seamless, since the user never notices when software functions are handed from one application to another [source: TConsult, Inc.]

An API resembles Software as a Service (SaaS), since software developers don't have to start from scratch every time they write a program. Instead of building one core application that tries to do everything -- e-mail, billing, tracking, etcetera -- the same application can contract out certain responsibilities to remote software that does it better.

Let's use the same example of Web conferencing from before. Web conferencing is SaaS since it can be accessed on-demand using nothing but a Web site. With a conferencing API, that same on-demand service can be integrated into another Web-based software application, like an instant messaging program or a Web calendar.

The user can schedule a Web conference in his Web calendar program and then click a link within the same program to launch the conference. The calendar program doesn't host or run the conference itself. It uses a conferencing API to communicate behind the scenes with the remote Web conferencing service and seamlessly delivers that functionality to the user.

Now we'll explain some of the technology that makes conferencing APIs work.